Read this story as it was first published in the April issue of Cruising World.

Finnish sailors are proud of their submerged rocks. They grinned as they told me about the many skerries that barely break the surface of the Baltic Sea.

“Surely most of them are well marked,” I begged.

They shrugged their shoulders in a worrying, non-committal way and gave a rueful chuckle, like someone who has learned their lesson the hard way.

Those rocks were on my mind as I helmed west through the Finnish Archipelago.

I couldn’t afford to mess this up. My Finnish friends had generously lent me their sailing boat, Valaska, for three weeks, no strings attached, and I didn’t want to betray their trust.

The island of Korpo was to starboard. I’d just dropped off the owner’s son after a two-day shakedown cruise out of Turku, during which I tried to memorise where all the switches, sea cocks and latches were, which bits to jimmy and which ones were jammed. Now the yacht was my responsibility, and nothing but the hull stood between the rocks and I.

“After this west cardinal there are three north cardinals in a row, and then a south cardinal,” my crew told me, sitting in the cockpit, paper charts on his lap, checking the veracity of the chart plotter. He looked worried.

“I see an east cardinal there…is that ours?” I stood up, straddling the rudder of the trim little H323, ready to turn either way at moment’s notice, my eyes scanning the water for the waves in the middle of nowhere that characterise skerries.

And so it would go for the next few hundred miles as we wove our way through the thousands of islands sprinkled across the Gulf of Bothnia. Our destination was Åland, a place I’d never even heard of until I’d begun planning this cruise.

When the owner first made his offer I proposed that I sail to Sweden and explore its famous archipelago. And as soon as the words were out of my mouth I sensed that this was not what he had in mind.

“Yes, you could sail to Sweden, but Finland has thousands of islands as well. You would have to pass right by Åland. Look it up, you might want to spend your time there instead.” There was raw nerve of competition between the Scandinavian neighbours, I realised.

They were right about this little-known corner of Europe, where berries grow wild, the sun stays high in the sky during summer nights and the fluttering Åland flag reminds visitors that Finland may own the land, but the hearts and spirit of the people remain free.

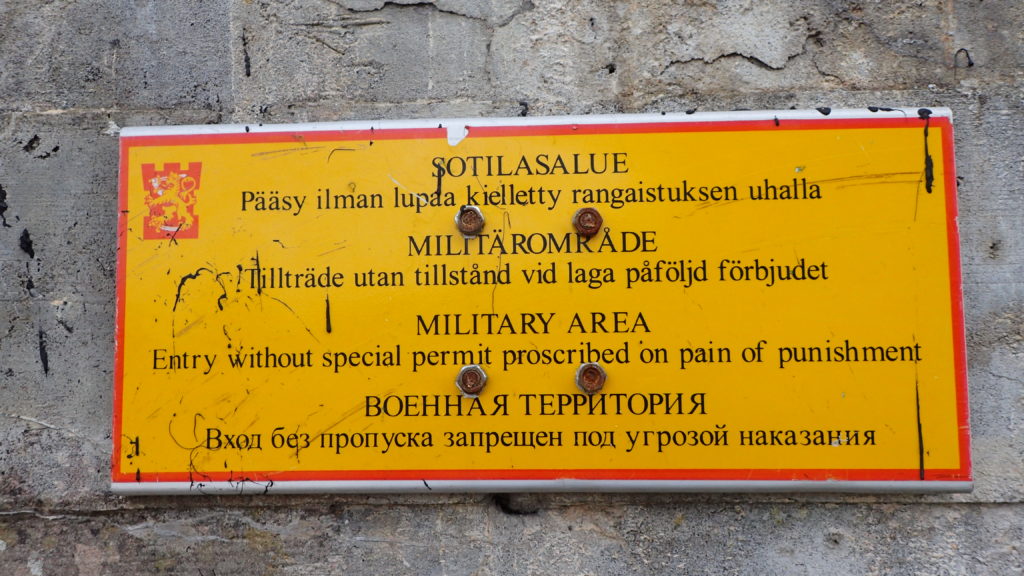

Åland is an archipelago of 6,500 islands and skerries. It was under Swedish rule for 700 years until the Treaty of Fredrikshamn forced Sweden to hand it, along with Finland, to Imperial Russia. In 1917 Finland declared independence from Russia and took Åland with it. Ålanders argued for their own self-determination, with a request for annexation by Sweden, but there were concerns that independence could make them vulnerable to Nazi Germany or Soviet influence.

In 1920 Finland granted wide-reaching cultural and political autonomy to Åland, including its own flag, postage stamps, police force and a seat in the Nordic Council. This demilitarised region is part of Finland’s Archipelago Sea, the largest archipelago system in the world and the spiritual home of Tove Jansson, the Finnish novelist and comic strip author of the Moomin books for children.

Dotted with natural harbours, remote islands and weatherbeaten pilot houses, Åland’s history is visible at every turn. In small ports I saw iron mooring rings pounded into granite shores by Russian sailors more than a century ago, which today are used to moor yachts. Lonely pilot houses top windswept islands and remind sailors that this was once one of the great shipbuilding sites of Europe.

It is rare to see sailors from outside Scandinavia in these waters, and most of those you do meet are German. So, when we arrived in the marina at the top of Bärö, next to the island of Kumlinge, we were surprise to find a dozen cruisers filling the tiny harbour. But there was still one spot left — arriving in a 32 foot boat with a 1.4m draft is a distinct advantage in these waters. These brackish waters have no significant tides, allowing for an extra degree of bravery when edging a yacht into shallow anchorages.

After the customary anchor drinks I changed into swimming shorts and headed for the sauna built on a floating dock, eager for the full experience of Finnish sailing. I threw open the door with a cheery “Hello!” — sometimes it’s an advantage to have everyone know you’re not local. The three women inside pulled their towels a little bit tighter around them and looked at me suspiciously.

“This is a private sauna,” one of them cooly informed me.

I stammered my apologies, backing out the way I’d come, and returned to the boat for additional anchor drinks. Soon one of them swam over with a smile on her face to explain that we had to book the sauna — but unfortunately it was already booked solid for the evening. Our first sauna experience would have to wait.

The next morning we returned to the steady southwesterly 15-18 knot breeze that had brought us here. It carried us to the remote northern shores of Fasta Åland, the main island, where the region’s most untamed forests and islands are. Saggö, nestled against its sister island Saggö ön, forms a narrow strait that provided us protection from the wind and showed promise ashore.

It was my first attempt at Finland’s unique mooring system. I motored along the shore to check depths, then picked my spot. The crew stood on the bow, mooring lines in hand, and I dropped the anchor from the stern as we approached the rocky cliffs. I edged the boat close enough for the crew to jump ashore, where they banged iron pitons into cracks in the granite. Mooring lines were looped through the pitons, while I tightened the anchor line. When we were done the bow of the boat was only two feet from the rocks, but the steep shore and taut anchor line kept the keel in deep water.

I jumped onto a boulder covered in orange lichen and scrambled up the rocks, using the scrawny fir trees to pull myself into the forest. The forest was deep and quiet, with only the sigh of wind against the tops of the fir trees to break the silence. The thick, springy silenced my steps. I reached down and pulled out a damp handful, releasing a woodsy, earthy smell — a scent I don’t normally associate with cruising holidays.

Then I spotted them…a cluster of red ones here, some deep purple ones there. Bilberries and lingonberries — in North America commonly known as blueberries and cranberries — growing wild in thick clumps.

I dropped to my knees and gorged on them. They were tart and sweet, making my tongue tingle. I picked until my fingers were blue with juice and had filled a small bag with those that somehow escaped my mouth.

That evening we sat around a campfire on the rocks, sipping coffee and eating fresh berries with scones baked in Valaska’s oven. The firelight flickered on her white hull, confusing me for a moment — was I on a camping or a sailing holiday?

We continued across the north of Fasta Åland, alone but for the Whooper swans — Finland’s national bird featured on the 1 euro coin — and even an occasional seal, but we saw few other boats. Eventually we turned south, down the western side of the island, past the Ådskär lighthouse to Mariehamn.

The southern coast is the part of Åland that most visitors see. Mariehamn, the region’s capital, was named for a Russian empress. Here huge ferries disgorge tourists from Sweden, Estonia and mainland Finland, and the streets are lined with cafes and restaurants in ornate, historic buildings. It’s home to summer music festivals and nearly half of Åland’s population.

That night the wind rose until waves broke over the marina docks and the air was filled with the screech of rigging, so in the morning we switched to bicycles, Åland’s other great mode of transport. Fasta Åland and the outlying islands have hundreds of kilometres of well maintained and signposted bicycle paths, and we followed one of them north. It took us through rolling fields of ripe barley and wheat growing between forests of fir and silver birch, past small farms with bright red outbuildings and summer cottages with stacks of firewood outside their doors. Every few kilometres the path cut back towards the coast, and I caught glimpses of the sparkling Baltic Sea.

Twenty-five kilometres later we arrived at Kastelholm, a Swedish-built medieval castle occupied by Finns, Swedes and Russians over the centuries. It was used as a prison and execution grounds in the late 1600’s when Åland was in the grip of a hysterical witch hunt. Åland’s independent postal office has just issued a stamp to commemorate the execution of seven suspected witches.

From the castle walls I looked down on the Kastelholm Yacht Harbour, nestled in the narrow inlet of Ladängsviken, making a mental note to sail rather then pedal next time.

By the next morning the winds were more manageable, and we set off through the complicated fairway leading from Mariehamn to open sea. We shared the channel with several massive international ferries, which added to the navigational challenge. Despite the apparent remoteness of the region, there are also small ferries criss-crossing the archipelago, requiring sailors to keep a constant watch.

Rödhamn, an island port I’ve heard about from numerous other sailors, is just 10 nm south of Mariehamn. Its name refers to the red (röd) colour of its rocky shores, which have provided safe haven to centuries of seafarers. The shores of the southern, sea-lashed side of the island are dotted with stone cairns left behind by passing sailors. There is no electricity or running water in the marina, making it a quiet, peaceful place. A small bakery delivers hot rolls to your boat in the morning.

But the real reason I came to Rödhamn was its famed sauna. Late that night we hiked across the island with our towels around our necks. The air had turned chilly and the sky was filled with the kind of clear light only found in a high-latitude summer night. On the far side of Rödhamn, perched at the tip of a peninsula, was a small hut facing the sea. Smoke puffed from its chimney.

We stripped and ducked into the warm darkness. It was nearly dark inside, with just a glimmer of evening light coming through a small window. The wood-burning stove hissed as I threw a scoop of water at it, producing a searing hot steam that rose to ceiling. Soon I was dripping with sweat and conversation ebbed to the occasional sigh.

When the heat became unbearable I burst out of the sauna and ran, stark naked, across the smooth granite rocks that sloped towards the sea. The indigo sky was streaked with yellow light, the sun still high above the horizon despite the late hour.

“Whoo hooo!” I shouted as I launched myself, my yell becoming a yelp as I hit the frigid Baltic Sea. Within seconds the cold became too much, and I swam for the shore to dash back into the sauna.

The summer was coming to an end, and the wind turned from westerlies to easterlies as we began our 150nm voyage to Valaska’s home port of Helsinki. The easterlies brought a cold rain that slashed at our faces as we tacked our way home, as if cajoling us to return to Åland and its sunny skies.

Follow

Follow