Read this essay as it appeared in the February 22, 2018 The Globe and Mail newspaper.

Dad’s raspy 87-year-old voice was filled with relief that this last bit of business was taken care of. But I also heard uncertainty, a tinge of seller’s regret, over the telephone.

“He’s agreed to the price and it’s a done deal,” Dad said, his voice muffled by half a world of telegraphic cable. “That’s it. That was my last piece of farmland.”

I was in Hong Kong when I received his call, a long way from Canadian land that he himself broke and turned into grain fields. The fields where my siblings and I learned to put in an honest day’s work, the cornerstone of our family farm on the Prairies. The land that had defined him as a Mennonite man, one chapter in our culture’s long history of buying wilderness and turning it into productive farmland. Selling his land meant he was exiting the cut-and-thrust of agri-business. It meant he no longer had a seat at the table when talk turned to crops and taxes, government subsidies and drainage plans.

When Dad bought half the half section, 320 acres we always called Section 10, it’s designation according to the Dominion Land Survey in the 1800s, it was mostly old-growth tamarack and spruce and the ground was covered in luxuriant moss. It was home to bears and bobcats, wolves and wild that would take years conquer. There were no proper roads leading to it, and just beyond it lay mile after thousands of miles of wilderness. It was low-lying peat and prone to flooding. The land was cheap because it was beyond the fringe of civilisation, part of a new agricultural frontier in Manitoba’s Interlake region. The government offered Dad favourable financing terms because he was a young man eager to help build Canada’s agricultural industry, to tame the nation’s vast expanse.

Grainy black and white photos in our family album show him and my mother, fresh faced and smiling as they began carving a farm out of the forest in the early 1950s. They were in their early 20s, poor but filled with the thrill of prospect. It was a grand adventure to them. One picture shows them resting in waist-deep snow while cutting down the pine forest to make room for their first crops, another has Dad on a borrowed bulldozer, pushing brush into long windrows for burning. Then there’s the photo of him standing in his first crop of barley, which grew as high as his chest but couldn’t hide his beaming smile.

“Ahh, those were hard times,” he says when he sees the pictures. “We worked so hard, because we wanted to build something, to have our own farm. That land was everything to us.”

Sold. Sold to someone I’d grown up with, a farmer who will take good care of it, but still, Section 10 is gone. We knew it was coming — he tried for many years to convince my brothers and I to buy it. But none of us wanted this particular piece of land.

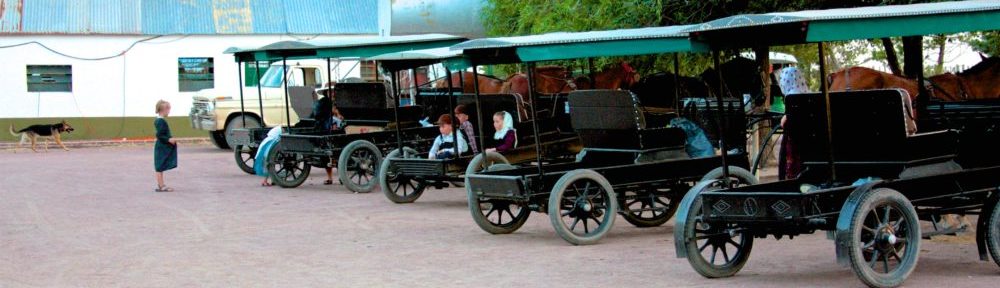

Most of my family still lives in Manitoba. I’m the one that has moved farthest away. When we gather near the farm we grew up on, and the heavy Sunday lunch has been consumed, the men pile into pick-up trucks and go for a drive down the rutted dirt roads circling Section 10. It’s always only the men — because land and crops is a man’s game. At least in a Mennonite’s mind it is. We drive and tell stories about picking roots and long hours on the tractor.

“Ohh, do you remember this corner of the field, the roots that we had to pick here?” one of my brothers asks. The truck slows down so we can get a closer look.

“We’d pick them and burn them, and every year the frost pushed up a fresh crop,” another brother adds.

One person driving the tractor, slowly pulling a flat bed trailer. The others walking behind, sinking deep into the soft peat, picking up the remains of the forest and hurling the roots onto the trailer. When the trailer was full we dumped the roots into piles and burned them. Rock picking wasn’t much different — just heavier to lift and harder to dispose of. Hour after hour of hard work, the earthy smell of the land permeating our hands and clothes, the dirt hiding thick in our hair.

“Child labour. That’s what that was.” Everyone laughs.

Dad squirms in his seat. “Ahh, it wasn’t so bad. And there was no other way, if you boys didn’t work hard the farm wouldn’t keep going.”

“We’d clear the fields of roots and rocks, and then it would rain too much and the fields would flood,” one of my brothers continues.

“It was all we had. We had do the best with what we had,” Dad says.

The stories are always about the struggle, the fight against nature. There were no easy gains made on Section 10. And that’s why none of the brothers bought the land. We wanted nothing more to do with land that required such hard labour. The land was important to our family history but owning it would put nostalgia above smart investment, and none of us could afford such costly sentiments.

Yet owning farm land is central to Mennonite identity. It spells security and stability and, most importantly, independence. Menno Simons, the radical 15th-century religious leader for whom the Mennonites are named, never called on his followers to own land. Nowhere is it written that Mennonites must buy and break land. But the faith’s key tenets of isolationism and simple living were translated into practicing agriculture in remote regions, places raw and wild enough that we could do as we pleased. So, for a Mennonite man, land means you don’t owe nothing to nobody. It means you’re your own man.

Mennonites like to tell stories about how we have moved from country to country to escape religious persecution, to find freedom to live the old way. But, truthfully, the moves are often about finding new land. And Mennonites are thrifty. Swampy land that needs draining can be had for cheap, and all it takes is hard work to turn it profitable.

Perhaps we’re influenced by our earliest roots in the Low Countries, where holding water at bay was a matter of survival. In the mid-16th century those skills earned us an invitation to settle, en masse, on the shores of the Baltic Sea. We dug ditches and built dikes, creating an agricultural haven. Then Catharine the Great invited us to move to southern Russia, promising us good land. We accepted, and took a break from our ditch-digging to farm wheat and silk worms on the well-drained steppes.

In 1874 my great-grandfather moved from Russia to Canada in the first wave of Mennonites to colonise the Prairies. He settled in the Red River Valley, where he needed those diking skills again. The Red regularly breaks free of its banks, overfilled with spring melt. In Rosenort, the diked village where both of my parents grew up, the farmers hold their breath every spring, watching the river rise, rejoicing when it doesn’t flood and resigned when it does. We’ve done it in southern Mexico, Belize, all the way down to Paraguay and Bolivia. On a topographical map, many Mennonite settlements are located in deep green territories, where the land dips and water gathers, places the cartographers mark with cross hatchings.

Dad added another chapter to that story when he left the Red River Valley and moved north to the boggy shores of Lake Winnipeg to break virgin peat land. For Dad, digging drainage ditches became as much a part of farming as planting and harvesting, from an annual deepening of ditches already dug with the tractor to hiring heavy machinery to transform the landscape, thumbing his nose at nature. Ditches that led the water off our land and towards Lake Winnipeg. In really bad years the lake flooded, snaking up those same ditches to drown out our barley and canola. Farming the Mennonite way.

No matter how many ditches we dug, the tractors and harvesters still became stuck. My father put rice tires on the harvester — although there was no rice being grown — hoping to better churn his way across his swampy fields. To no avail.

My childhood memories of farming centre around being mired axle-deep in the fragrant peat of Section 10, the tracks filled with seepage. Deep ruts, so deep you had to scramble to climb out of them. I could think of a hundred things I’d rather be doing.

“Why are we farming here? This is the worst place in the world to farm,” I’d say, my hundredth complaint for the day as I grudgingly helped Dad work the land.

“It’s good soil, we just need to drain it better,” Dad said. He slapped at the hordes of mosquitos — ohh, there were mosquitos, big and by the thousands. He crawled through the muck under the harvester to hook a logging chain to the axle. I took the other end of the chain and dragged it towards the idling tractor, hitching the machines together with the clinking steel snake.

“Now start slow. Don’t yank it or the chain will break,” he would instruct.

I crawled into the tractor cab, twisting around in the seat to watch him on the harvester, watching his hand signals. I revved up the big diesel engine until it belched black smoke, eased out the heavy clutch so slowly that my skinny legs quivered with tension. Watching Dad, watching the harvester, the chain, a delicate dance of lumbering beasts. The chain pulled taut and then, instead of the harvester popping out of its hole, the tractor’s spinning wheels dug giant holes in the quagmire, pulling the machine deeper and deeper with every revolution.

I could see my father shouting, urgent, his lips moving but words drowned by the roar of thrashing pistons. He waved his arms for me to stop. I groaned.

“I’ll put another drainage ditch through here and then next year it will be dry,” Dad said as we unhooked the chain and repositioned the tractor on firmer ground. But it was never dry. Some years we had to wait for frost to firm up the water-logged fields before the crops could be taken off. In those years harvest became a race against the snow.

“I’m never gonna be a farmer,” I told him, more than once, as we stood knee deep in bog, working to free the machinery. I said it angrily, with vengeance.

And I stuck to my word. I moved away from the farm and the Mennonite lifestyle that the rest of my family still shared. I lived in Chicago, New York, Singapore, London and Hong Kong, moving further and further away from my Mennonite identity. I certainly didn’t attend a Mennonite church, I rarely found opportunities to speak our quirky Plattdeutsche mother tongue, and digging ditches made for good stories in the bar, but it was no longer a part of my life. I’d scrapped that muck from my shoes for good.

Then, years after I’d left and Dad had long ago accepted that I wasn’t the farmer he’d hoped I’d become, on a trip back to Manitoba to visit my family, I told Dad I had some money I wanted to invest. His eyes lit up and he leaned forward in his chair.

“Hey, there’s some land for sale near here,” he told me. “It may not go up in value as fast as those stock markets do, but it will always be there. They’re not making more land.”

The language of land — drainage, fences, good soil, stoney or not — was one I’d never learned to speak. But the idea of owning land, my very own land, still appealed to me. It appealed to the Mennonite in me. I’d thought the Mennonite in me had faded, replaced by urbane tastes and international lifestyle, so I was surprised at how his suggestion struck a chord in me. Drifting through the world’s capitals earning a living with my pen was good fun, but owning land, now that was permanence. That was long term planning, building something for the future. The advertised plot was a few miles from our family farm. It was cleared of trees, already tamed and well drained. No digging of ditches needed. It promised an easy, painless path to becoming a respectable Mennonite man.

So I bought the land with a loan from the home town credit union, a small place, where my family had banked for so long the manager still recognised my voice on the telephone. It was with great satisfaction that I took the “For Sale” sign off the gate and walked into the field for the first time.

I kicked a clod and thought, “That’s mine.” I eyed the slope towards the lake, pretending, for a moment, that I knew something about land. I had friends and family that owned thousands of acres so there was a tinge of city-boy sheepishness to my pride in owning this modest plot. I knew I was reaching back to something that wasn’t me anymore, that I had skipped some important steps. I hadn’t broken my own land, planted it with crops, let the land tether me to a place, a community, church and family that consumed me all day every day for my entire life. It wasn’t the same as what Section 10 had done for Dad. This land had not been watered by sweat from my father’s brow. It did not come with stories of hardship, work and progress. And I’d never be a real farmer like my Dad. But I did have a piece of my own land.

Solid, well drained land, and it’s not for sale.

Follow

Follow